Introduction

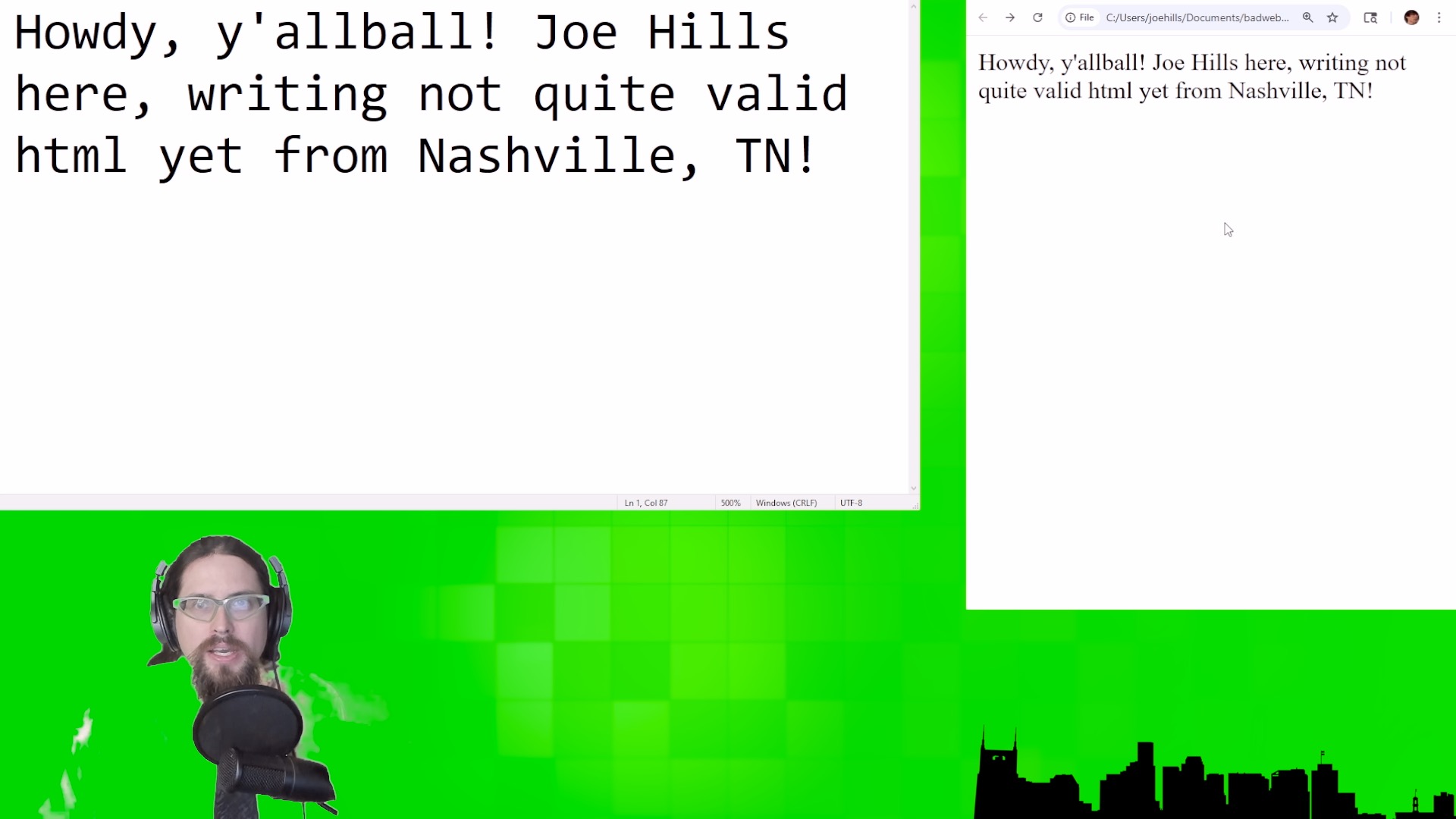

Howdy, y’all! Joe Hills here, recording as I always do in Nashville, Tennessee, and in today’s lesson we’re going to learn how to go from a bad web page to a simple web site.

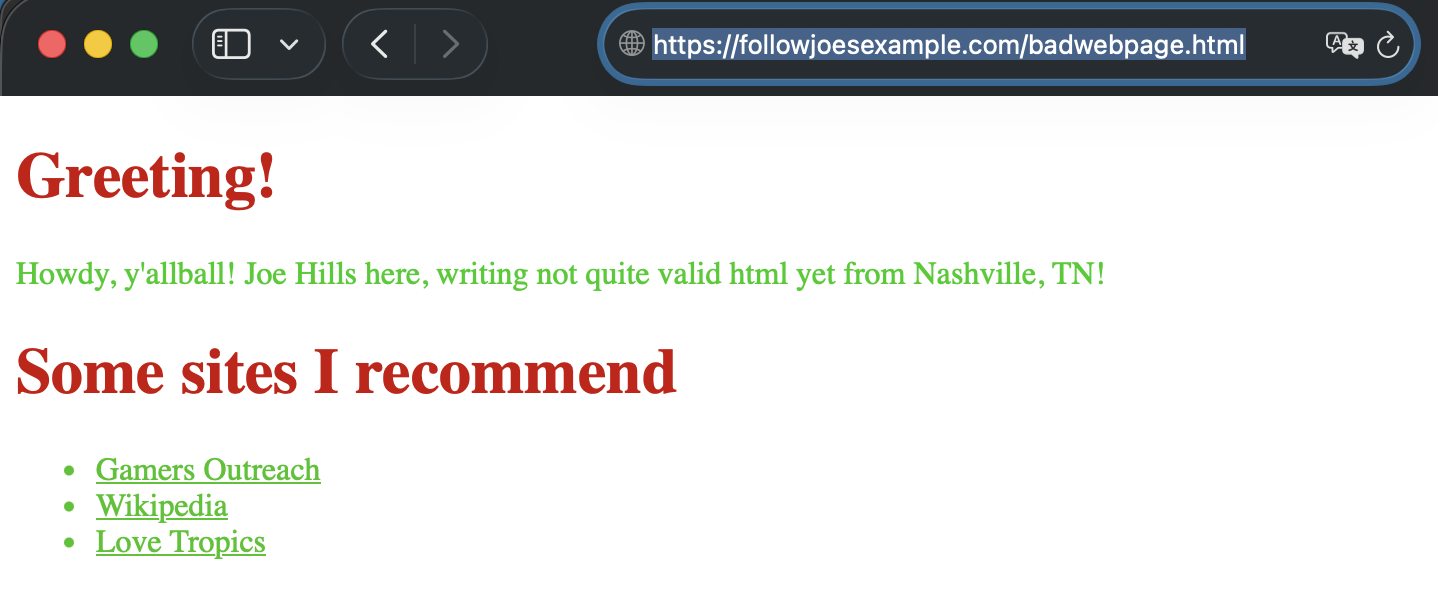

Everything we’re doing today builds directly on our previous two lessons. In lesson one, we created a single-file bad web page, and in lesson two, we learned how to copy that web page to your web host’s server in its web root directory.

What is a web site?

If you wanted to, you could just code a bunch of individual and unique bad web pages, upload them to your web host’s server, and then send folks links to each page directly via social media or e-mail… but a bunch of web pages isn’t a web site in the same way that several plastic bags of meats and cheeses isn’t a charcuterie board, or several vertebrates with polyhedral dice isn’t a D&D group.

A web site has a couple aspects that unify its individual pages into a single experience for a visitor:

- First, a logical information structure

- Second, consistent visual design

Wow, both of these sound equally fun, so I’m just going to work my way down the list, starting with logical information structure, woo!

Logical information structure

I hope you brought your cartography tools, because we’re about to sketch out a site map!

The index.html page we created last lesson will serve as our home page, and will welcome visitors to your site and direct them toward the other information you’d like to share.

What kind of information would you like to share? Only you know the desires of your heart, but I will share with you those of my own!

I’d love to have a web site where I feature different projects as I work on them!

So, I have a couple projects I’m working on right now, a thatched-roof hut that sells potatoes, and an art deco TV studio. I also want my website to include a quick bio about me in case visitors who read about my thatched-roof hut want to learn more about me.

So that brings our site map to four pages including the home page. The fastest way to create a page for each of these concepts is to copy my index.html file three times. I’ll name the first one as potato.html, the second one as tv.html, and the third ones as bio.html.

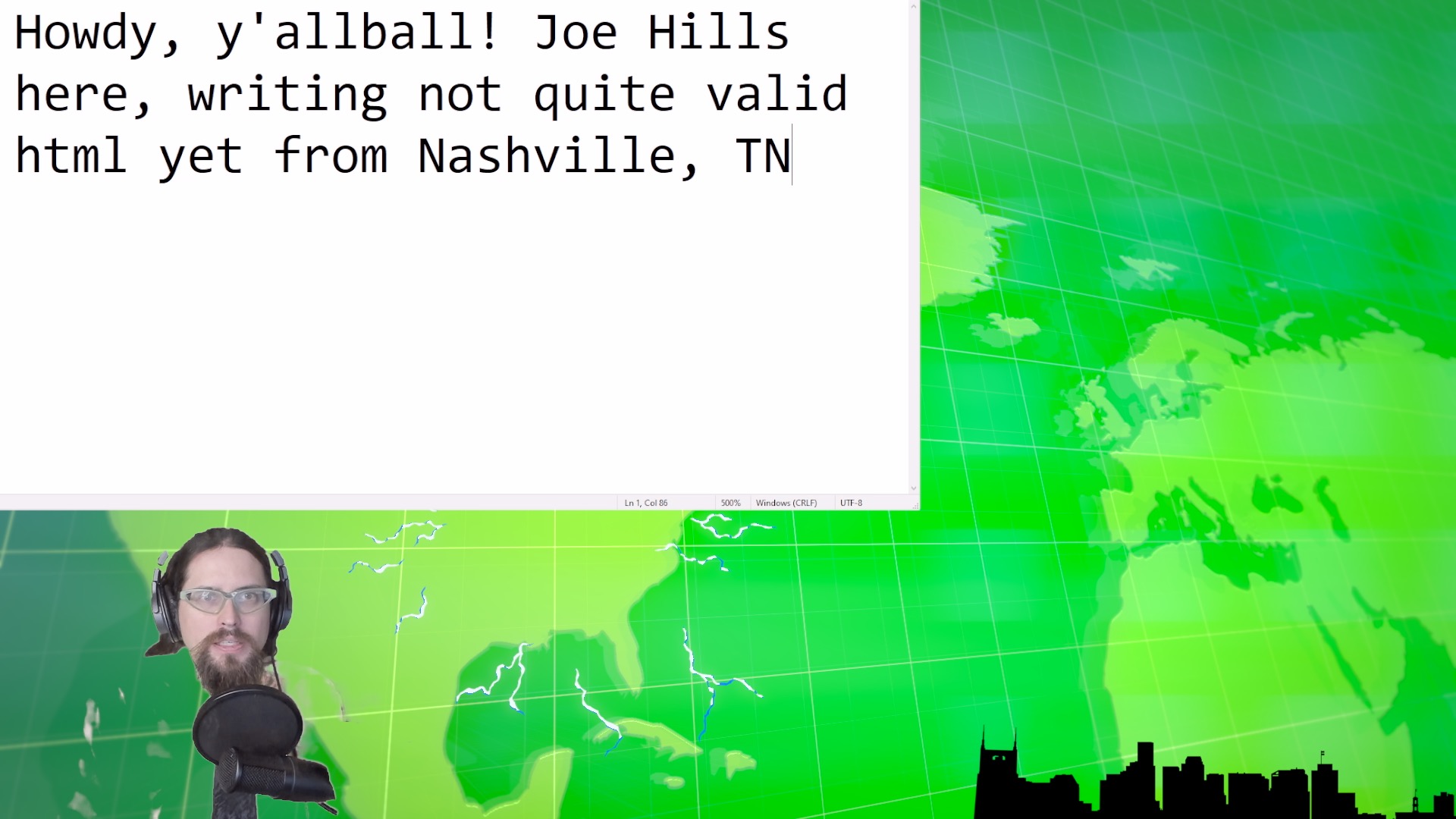

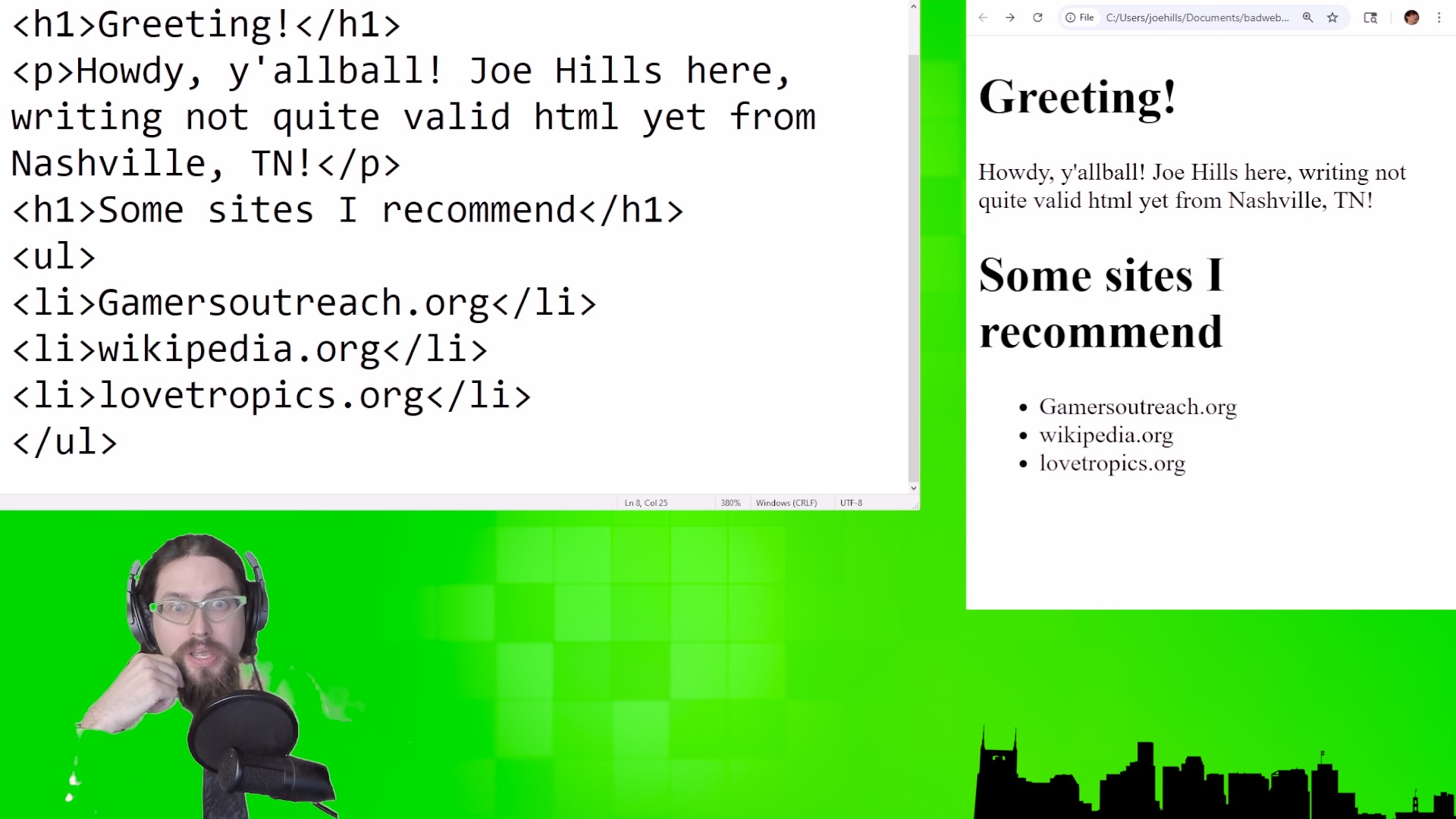

If we open each page, we can update the text in the <title> tags, the headings in the <h> tags, and the body text in the <p> tags to reflect our beautiful imaginings we’d like to gift to the world!

Navigation

Now that we have four pages, we need to create a list of links that will point to each page, and add that list to all four pages. Since all of the pages are on the same domain name, we can use urls that are “relational” and start each one with a slash rather than the full domain name.

So, between our page’s heading and our body text, we’ll add that list of links here, and then we’ll upload all four pages.

Okay, so now we have a logical information structure with four pages and they already all have the same visual design, so you’re probably wondering, why do we need a separate heading for…

Consistent visual design

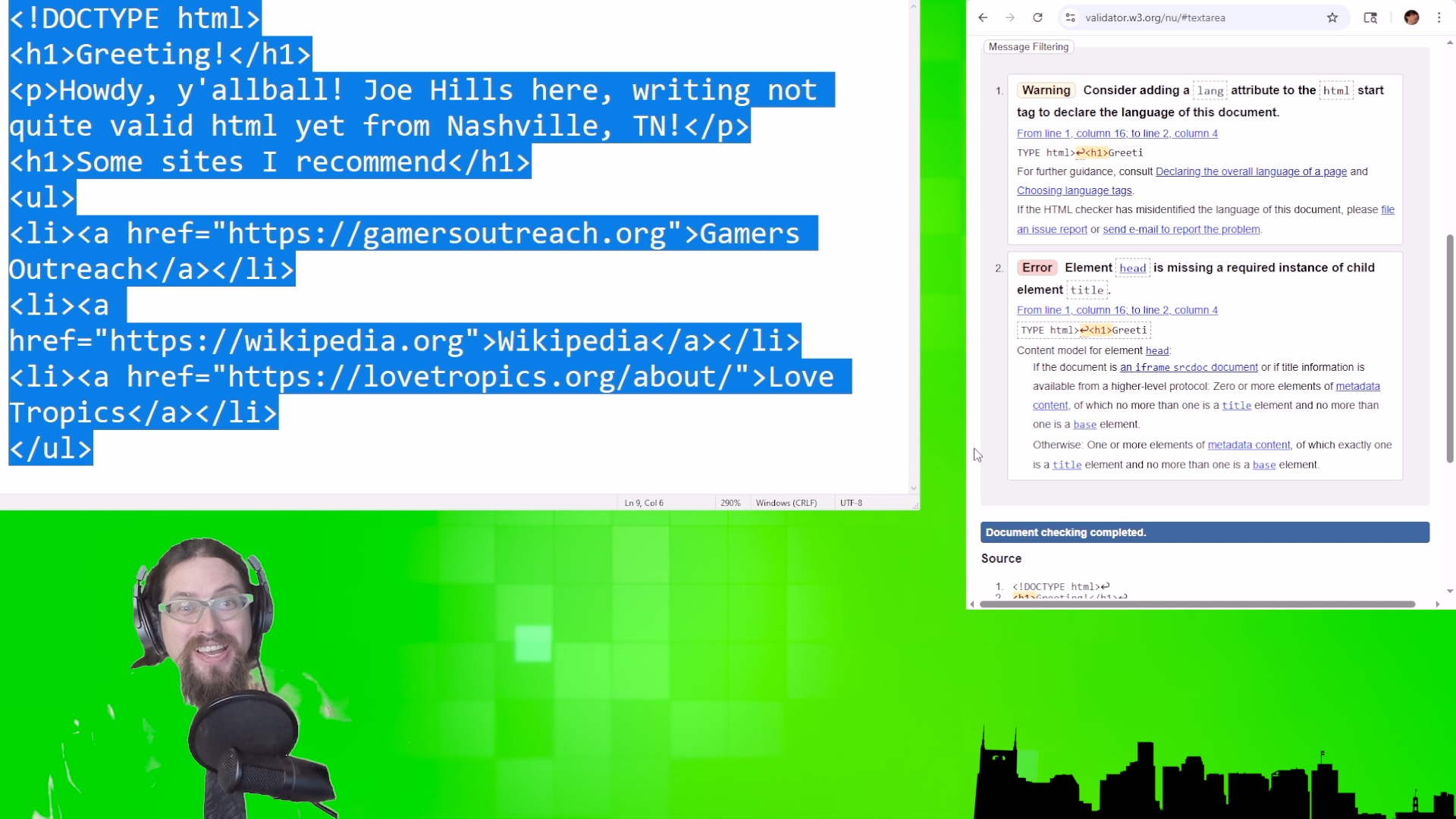

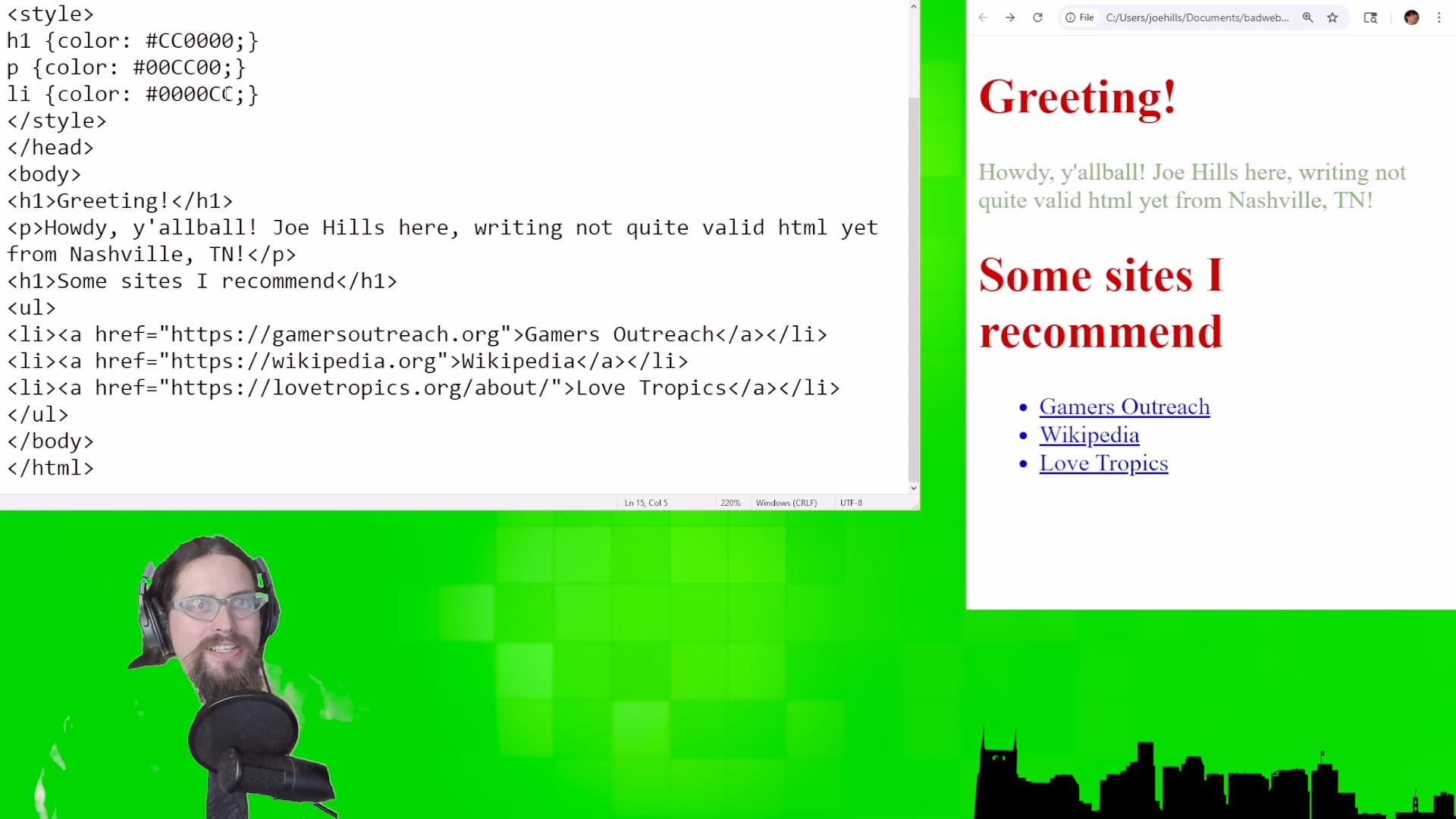

Right now, we have one web site, with four separate files for four separate pages. Intuitively, you might think this is the optimal number of files for a four-page website, but as soon as we make a style change to one, say turning the headings a more readable color, or turning the body text a more readable color, or adding margins on either side of the body text, we’ll have to make those same changes four times!

Stylesheets

That might not sound like a lot now, but what if I want to add more pages for more projects over time, or additional biographies of myself, because if George Washington can have dozens, maybe I can have at least two as a treat? So, we could have a dozen pages, or dozens of pages, and we want to create one file that stores the style code for all of those pages.

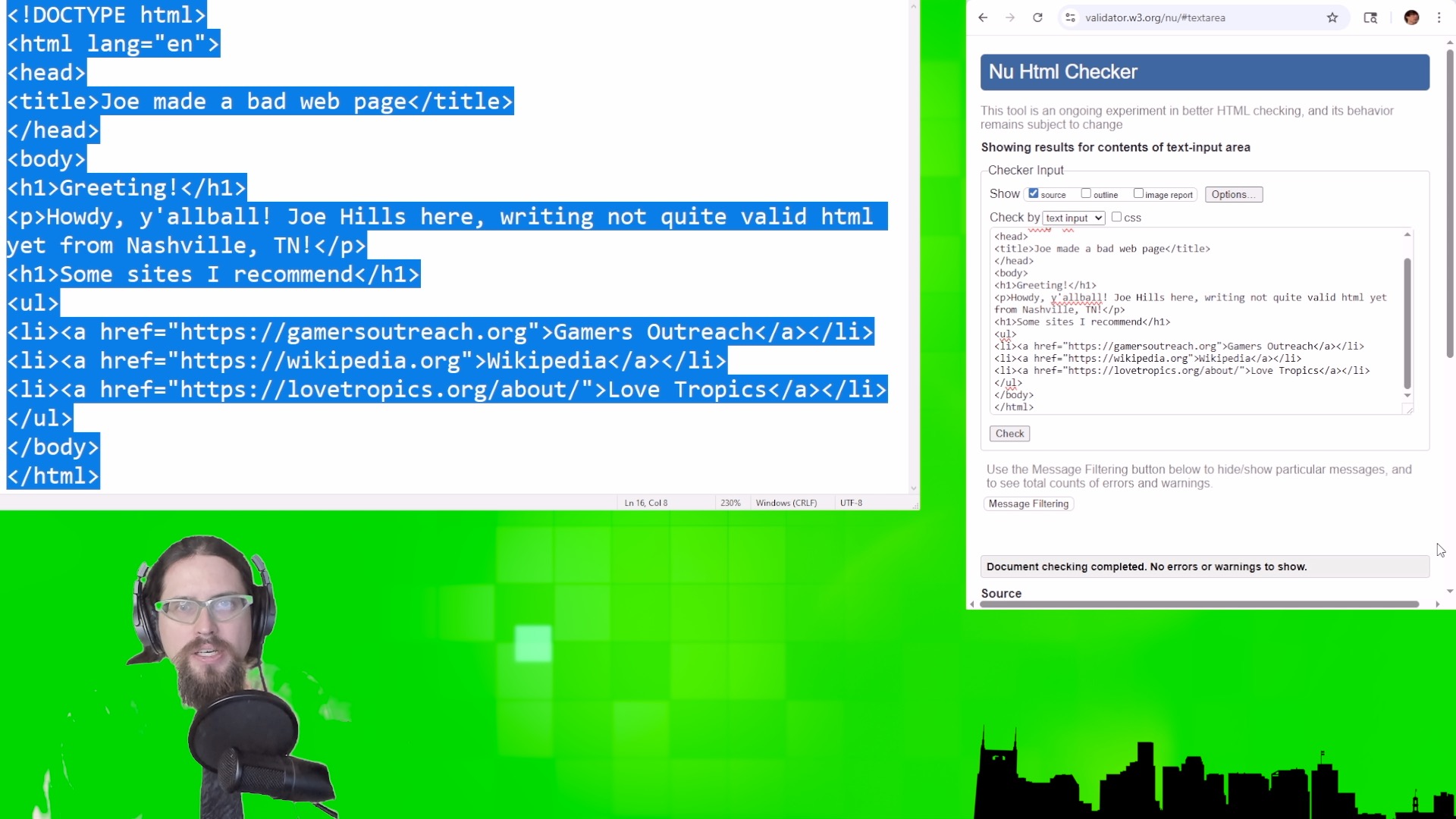

To do that, we’re going to create a new folder, called styles, and then take the style code from the top of our homepage, create a new type of file called a stylesheet, name it “style.css” and upload it in that folder.

Then, we’ll remove the code in the <style> tags at the top of our four pages and replace it with a linked reference to our stylesheet using the <link> tags.

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/styles/style.css">

We’ll indicate using the rel attribute that the relationship between our page and the linked file is that of a majestic stylesheet, and we’ll use the href attribute to set the path and filename to “/styles/style.css” and wowed-woo, we have saved our future selves a ton of work.

We can apply this methodology to fonts and images we want to host as well.

Fonts

The Alphabet subsidiary Google has a bunch of fonts on their servers you can link directly, and smaller font companies like Nate Piekos’s one-man foundry Blambot will sell you fonts you can self-host in a fonts directory comparable to the styles directory we created earlier. Anyone who sells fonts will give you specific instructions about how to use them, but it’s really all the same as linking a stylesheet: your web page will tell the browser to pull in an external resource to make the page display the way you’d like.

Images

When it comes to images, you’ll probably want to host quite a few of these, so, creating an images folder to host them all in is generally advisable. I’m not your boss, you can put them all in the web root directory for all the browsers care, but making this one extra directory now may serve to make your life easier three years from now when your site is thriving after dozens and dozens of updates and expansions.

Okay, so let’s say we want to add images to our pages, we’ll use the <img> tag for that. There’s a whole slew of attributes available for every tag, and <img> is no exception, but the ones we care most about right now are the src attribute, which provides visitors browsers with the URL it can find the image at, the alt attribute which describes the image for screen readers, and the height and width attributes, which we can safely set to “auto” and “100%” until we know better, which is a rabbit hole wildly out of scope for today. Almost every attribute of every html tag could be its own video, and with good reason, but we’re on a bit of a focused path toward self-publishing a website here.

So, here’s a photo of me I can add to my biography page. We’ll upload it here and add relevant attributes to our <img> tag like so…

<img

src="/images/joe-bio.jpg" alt="a photograph of Joe Hills

staring into the distance"

height="200px"

width="auto">

And wow, we have gone from a single web page to an entire web site!

Outroduction

For some people whose sites only need a few pages and won’t be updating regularly, this is all you need, but for folks who want a blog or to update regularly, you’ll wanna return for Lesson Four, in which we’ll cover content management systems like WordPress and whether you should make that jump in complexity in return for ease of updating.

Whether you’re using hand-coded html or WordPress, I recommend you consider our sponsor NameHero for your hosting needs. They do both!

If you need hosting or a domain name, please make your purchase using my affiliate link at:

Until next time, y’all, this is Joe Hills from Nashville, Tennessee. Keep adventuring!